Site Tools & Extras

Quick Links

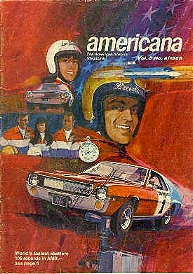

American Motors eXperimental

AMX Record Setter in 1968

Even before the car's official dealer and public introductions, the AMX shattered 106 records at the hands of Craig and Lee Breedlove and their assistant Ron Dykes. In a series of spectacular high-speed runs, eight international, sixteen national, sixty-six American closed car, fourteen American unlimited and two national unlimited records were broken.

On December 1st, 1967, Craig Breedlove was contacted by AMC performance activities manager Carl Chakmakian to discuss putting the AMX through its paces. What better way to promote the car than to have it attempt to set new speed and endurance records before it even hit the streets, and at the hands of such a speed expert as Craig Breedlove.

The deal was finalized and Breedlove received two cars at his shop in California on December 17th. The normal preparation time for such a car is about six months, AMC gave him less than six weeks.

The two cars that were delivered were identical AMXs with the exception of the engines. One was a 290 V-8 for class C, and the other a 390 for Class B. The engines were pulled and sent to Traco Engineering for blueprinting. The 290 was bored to 304 cubic inches and the 390 to 397 cubic inches. The cars were equipped with exhaust headers, eight quart oil pans, oil coolers, hi-rise intake manifolds, racing camshafts with solid lifters and stronger springs. The 304 used a Holley 4-barrel, the 397 a larger Holley 3 barrel. The chassis was prepared as well. All parts were Magnafluxed for cracks. Goodyear racing tires with safety innerliners were mounted on Mag racing wheels. Heavy-duty factory front and rear springs were installed along with rear spring traction control arms, heavy-duty shock absorbers, rear axle coolers and a panhard-type track in the rear to eliminate side sway. A roll cage, instruments and modified bucket seats completed the interior. A thirty seven gallon cell-type safety gas tank for the sustained 24 hour speed runs was installed in both cars.

To keep the cars from becoming airborne at such high speeds, the front ends were lowered, the hoods were slanted down and spoilers were put on just below the front bumpers. All times would be supervised and sanctioned by a crew of the USAC ( United States Auto Club ). This crew also inspected the cars thoroughly and set up their timing equipment.

The 304 car would be the first to run and would be shooting to run over 150 mph, the 397 car would attempt in excess of 175 mph.

The 304 car started off good, but little things began to happen. It lost a fan belt, which required a ten-minute fix in the pits. While Lee Breedlove was driving at 156 mph she complained the car wasn't handling as good as it should, but that it was nothing to worry about. When she came in for her normal pit stop it was found that she had been running on a flat tire and only the innerliner had kept her from spinning out. This was a tribute to the AMX's excellent handling characteristics.

During Craig Breedlove's portion of the run with the 304 Class C car the alternator failed, dimming the headlights while the engine started missing. All this after sundown, and with only one hour to go for the twelve-hour record! He decided to go on because pitting would have cost him the record. Kerosene-burning lights and the headlights from parked cars illuminated the way around the track while he traveled at over 150 mph. The twelve-hour record was broken. The batteries were changed throughout the night instead of the alternator, which meant slower speeds. In the end it did not matter, Breedlove still managed 140.790 mph, covered 3,380 miles and established ninety new records with the C car.

Several days later the 397 powered class B car took the track. Things were going good until shortly after the eight hour mark when the car was burdened with transmission troubles. The 175 plus mph speeds combined with a bumpy track made the wheels go airborne every time they hit a bump. The added load when the tires came back down was too much for the transmission to take. By the time it was changed, bad weather had set in. Both cars were destined for the February 23, 1968 Chicago Auto Show, so the rest of the test had to be aborted. Even in the abbreviated eight hour test, the class B car set sixteen records, and the class C car set ninety new records. In all, 106 speed and endurance records were recorded by the AMX before it had even run on the street as a production car for sale to the public. That's every record in the book from 25 kilometers to 5000 kilometers. From 1 hour to 24 hours. From standing starts and flying starts.

Here are a few specifics: In class C the AMX's average speed for 24 hours was 140.790 mph. The old mark was 102.310 mph.

In class B, for 1,000 kilometers standing start, the AMX averaged 156.548 mph. The old record was 148.702 mph.

For 75 miles flying start it averaged 174.295 mph. The old record was 172.160 mph.

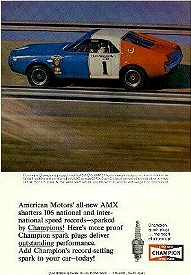

The number 1 Breedlove AMX as it is today.

Here is more information on these record setting runs.

By Craig Breedlove.

It takes skill, teamwork and superior equipment to run for records in auto racing. And it helps if you have a sense of humor, an iron constitution and plenty of good luck.

We were fortunate to strike just the right mixture of all the necessary ingredients when we went after, and set, 106 American and International speed and endurance records with American Motors' exciting new AMX, a few weeks ago at a test track in south Texas.

In many ways, the performance of both cars involved in the record runs was astounding, considering that the AMX was untried at the time. It was like kicking a freshly born eagle out of its nest. There was no cause for apprehension, however. This eagle soared.

Just looking at it, the AMX showed outstanding potential. Aerodynamically, it had the clean lines of a racer. Like our jet car the "Spirit of America" in which my wife, Lee, and I set the land speed records for both men and women, the AMX was my kind of racer-sleek and surefooted, with supersensitive handling characteristics.

One trip around the American Motors test track proved it to me.

The plan was to run two cars and I was anxious to get started. We decided that one was to be powered by a 290-cubic-inch engine and the other with a larger, faster and more powerful 390-cubic-inch powerplant.

We would seek to set American, National and International Closed Car records, as well as American and National Unlimited records.

The speeds: in excess of 150 miles per hour with the small engine and more than 175 mph with the larger, all sustained over long periods of time and closely supervised and sanctioned by a crew of United States Auto Club officials.

I knew one thing for certain. The cars could do it. I felt sure that the crew I selected to prepare, service and test the equipment would be equal to the machinery. The biggest problem was time. In our record runs in the jet car at Bonneville Salt Flats, we usually allotted at least one year to prepare our challenge. But according to American Motors' timetable, we had to be ready to hit the track with the AMX in six short weeks. It could be done all right-but only by working 90-hour weeks. We accepted the challenge. Why so much time? Well, you don't just take a stock automobile off the dealer's showroom floor-no matter how big or expensive the car - and go roaring full bore around a race track for 24 hours.

Two brand-new AMXs were shipped from the factory to my shop in Torrance, California. The engines were pulled immediately and sent to Traco Engineering to be expertly "blueprinted," meaning every part was sight-checked and even X-rayed to make sure the clearances, tolerances and other technical specifications were met to the letter.

The only departure from "stock" was a slight overbore on both engines to make them a bit more powerful. The 290 was bored out to 304 cubic inches and the 390 to 397 cubic inches. Not much. Just enough to give some added zip for the long stretches at high speeds.

For the car buffs among you, we also replaced the stock cast iron manifolds with exhaust headers; enlarged the oil pan to eight quarts and added baffling to keep the oil around the pump pickup; and installed a Holley four-barreled carburetor on the 304 engine, while the 397 was fitted with a larger Holley three-barrel. Both carburetors were mounted on high-rise aluminum intake manifolds. A racing camshaft with solid lifters and stronger springs replaced the stock setup.

The chassis then was ready to be set up for maximum performance at high speeds. As with the engines, all of the critical parts were X-rayed, or Magnafluxed, to make sure they did not contain hidden defects.

At high speeds and over long distances, a race car is like a chain - only as strong as that weakest link.

A faulty gasket on a radiator cap, or a bolt which has not been tightened that final half-turn, could cause an incident which would ruin long weeks of painstaking preparations. So it is imperative that the checks must be super thorough.

The preparations went smoothly. The stock steel wheels were replaced with mag racing wheels, not so much for strength but to increase the rim width to accept the wide Goodyear racing tires. The tires, of course, were equipped with safety innerliners which had more than proved their worth in stock car racing.

Heavy-duty front and rear springs, part of the factory's optional handling package, were installed along with rear spring traction control arms, heavy-duty shock absorbers and a "panhard" type track bar in the rear to eliminate side sway.

Inside the car, a full roll-bar cage was installed for driver protection and the stock bucket seat was modified slightly to give additional body support. A full set of engine instruments were added so that the driver would know constantly how the powerplant was performing.

Engine and rear-end oil coolers already had been installed along with a 37-gallon, cell-type safety gasoline tank. That was it for the inside.

Our car preparation was assisted by an initial meeting with Ronnie Kaplan Engineering in Chicago, which was well into preparing two Javelins for the SCCA Trans-Am sedan racing circuit

The outside of the car needed only a few touches. As I said before, the AMX has low, clean-cut and uncluttered lines that flow smoothly from the bumper-grill combination to the rear deck. They create a minimum of power-stealing drag or turbulence at high speeds.

The problem was not to make our eagle fly, but rather to keep it on the ground. If we had run the AMX at 175 mph as it came from the factory, it might have acted like an airplane wing, forming an area of lift over the car's top which might have caused it to literally flip over backwards.

So we lowered the front end slightly, slanting the hood down, and put a "splash pan" spoiler just below the front bumper, so that the air pressure at high speeds would act, instead, to force the front end down and keep the car on the ground.

When we were satisfied that all systems were "go", we trucked the cars to Texas. The track was a perfect circle, five miles in circumference, with enough cactus, rubble, dirt and sand for a John Wayne movie set. It was 20 miles from the nearest town, but although we tried to keep our record attempts as quiet as possible, it seemed we never lacked a crowd of onlookers.

For several days there was nothing to see. Rain, sleet, snow - you name it, it fell. The drivers in the tests were to be myself, my wife, Lee, and a west coast sports car racer. The USAC officials inspected the cars with a fine-tooth comb, set up their timing equipment, and pronounced us ready for the certification runs. But the weather wouldn't cooperate.

It was so frustrating that one day when bad weather closed the track, Carl Chakmakian, American Motors performance activities manager, and I took one of the AMXs out on the highway for a quick test.

Finally, the weather broke and the forecast was for clearing skies. But the weatherman said it might only be for a couple of days, so we hopped to it.

As I said, the track was a perfect circle-no straightaways-but there was a noticeable downhill side. You could sense the drop along the backside away from the pits. If the engine was running at 5,400 rpm's passing the pits it might jump to 5,800 on the other side of the circle as the terrain dropped perhaps 50 feet.

We had checked the elevation of the area so that the carbs could be set for best gasoline performance and, for good measure, we even mounted two complete sets of rain tires and had them ready to put on.

The class C car, the 290 stock engine, was the first to run. The plan was to go as hard as possible for 24 hours. We had been up for 48 hours getting ready. The last 24 was going to be something.

At the outset the car ran beautifully. Then little things cropped up. First we flipped a fan belt and the car was buttoned down in the pits for 10 minutes while it was fixed. Later, with Lee tooling around each lap at about 156 miles an hour, she complained that the car wasn't handling as smoothly as it should.

But she decided it wasn't enough to worry about, so she waited for her normal pit stop. When we checked the car then we found that Lee had been driving on a flat tire -that only the safety innerliner had kept her from a disastrous spin-out.

That attested pretty well to the handling characteristics of the AMX, all right.

My portion of the run with the C car got pretty hairy. The test was going perfectly when, just after sundown, the alternator failed, the headlights started to fade and the engine began missing. I had just over one hour to go for the 12-hour record. If I came in for a pit stop, the time required to change an alternator or a battery would cost us the record. I decided to go for the record and turned off my headlights to save power. I figured, with luck, the battery would supply enough current to run the engine for the necessary time. I could afford the pit stop after we had reached the 12-hour mark because the records were much slower after that time. I pulled the car down off the top of the bank toward the inside of the track, because there was no guard rail and I was afraid that without lights, I might go off the top of the track.

We had kerosene-burning "flameboes" every 500 feet around the inside of the track and placed every available car at points along the five miles to help illuminate the way with headlights. Traveling at 155 mile per hour in the dark presented some anxious moments but we managed the 12-hour record.

When I came in for my pit stop we decided to change batteries at each stop through the night instead of replacing the alternator. The battery changes meant slower speeds, but in the end we still averaged 140.790 miles per hour, covered 3,380 miles in the C car and established 90 new records!

We had run from 9:05 a.m. one day until 9:05 a.m. the next and we were dead tired. On the way back to the motel, one of my crew and I found a little stray black dog. We named it "AMX" and took it back to the motel, gave it a bath and fed it the only thing we could find- a chicken dinner. That was our victory celebration.

Several days later we geared up for another test, this time with the larger engine Class B car. And for a while it seemed that it would be even more successful than the C.

But shortly after the eighth hour, just when we were getting into the groove of the track, the car experienced a gearbox failure. The 175 mile-an-hour speeds and a slightly bumpy track made the wheels go airborne every time they hit a bump.

The added load when the wheels came back to the track was too much for the transmission. By the time we got it changed, we had run out of good weather again.

Because the cars were committed to the Chicago Auto Show, and by this time the AMX was much in demand across the country, we had to scrub the rest of the test mission.

What did we prove? Even in the abbreviated eight-hour test, the Class B car set 16 records. Between them the two AMXs rolled up 106 speed and endurance marks.

Not bad for a car that hadn't even run on the street.