Site Tools & Extras

Quick Links

1968-1972 Trans-Am Racing

Trans-Am Racing 1970

Roger Penske - Mark Donohue Car #6 - Peter Revson Car #9

"1970 was an unusual year, and part of it was, it was unusually good". Quote from Jim Kaser, Director of Professional Racing for S.C.C.A., in the AMC film "Trans-Am 70".

Two new entries debuted in 1970. Dodge Challenger and Plymouth Barracuda. Their involvement would make it six full factory teams slugging it out for the championship.

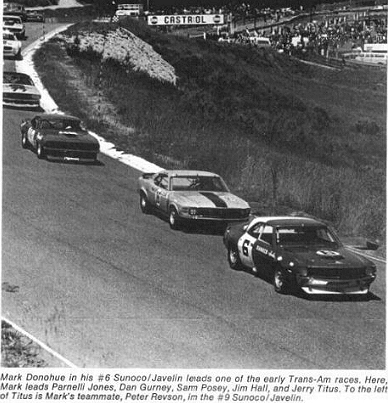

1970 brought many changes to American Motors. A new team owner, Roger Penske, with drivers Mark Donohue and Peter Revson would breathe new life into the quest to bring the Trans-Am Championship to AMC. Parnelli Jones and George Follmer would head the Ford Team, Jim Hall, Vic Elford and Milt Minter would drive the Camaros. Swede Savage would drive a new Barracuda with Sam Posey in a Challenger.

The Rules for 1970

The general rules governing the Trans-Am series are relatively simple. It is only when one gets specific about permitted optional equipment and the like that the rules get very complicated.

Here are some of the general operating rules for this and the 12 other Trans-Am races in 1970:

* The Trans-Am is a manufacturers' championship series in which points for the top six cars in separate over-2-liter and under-2-liter races are awarded to the car manufacturer not the driver.

* Points are based on nine points for the winning make of car, six points for the second place auto (provided it is not the same make as the winner), four points for the third place finisher, three points for fourth place, two points for fifth place and one point for sixth place. Only the highest finishing car of each make gets points.

* Each manufacturer may count the best nine finishes of the 13 Trans-Am races. The over-2-liter races must be at least one hour and 45 minutes, while the under-2-liter races must be at least an hour in duration.

* To be eligible, either 2500 of the same model or 1/250th of the previous year's production-whichever is greater-must be produced. The maximum wheelbase allowable is 116 inches and the minimum weight for the big cars is 3200 pounds with fuel and without the driver.

* Competing cars use pump grade gasoline. Class A (over-2-liter) cars are restricted to 22 gallon tanks, while Class B cars may not have tanks over 15 gallons.

* Each car must have an onboard starter and start by its own power. Only the driver may repair a car when it stops out on the course, and he may not push the car.

* In qualifying, it is the driver/car combination which earns a given time. Times are recorded on each lap for each car during qualifying.

* Pressure activated and/or elevated refueling tanks are not permitted this year. Contestants must use an SCCA-approved fueling can.

* And, finally, to be considered a finisher, a car must cross the finish line no more than five minutes after the winner has taken the checkered flag and must have completed half the distance of the winning car.

The Javelin Team

Mark Donohue - Media, Penn. - Age 33 - American Motors Javelin

Mark Donohue might well be called Mr. Trans-Am. He drove the Penske Camaro to 10 wins in 13 starts during the 1968 Trans-Am, then, in the tougher competition of last season, copped first place seven times and second twice in 12 starts. The Donohue Penske Story, of course, changed drastically this year when Chevrolet dealer Penske made a deal with American Motors to campaign their cars. Donohue, an engineer, is equally at home in the shop or behind the wheel. A protege of the late Walt Hansgen, Donohue is one of the hottest properties in U.S. racing. He and wife, Sue, live in the Philadelphia suburb of Media with their two children.

Peter Revson - New York City - Age 30 - American Motors Javelin

Pete Revson got the racing bug while in college, quitting first Cornell, then Columbia, to go racing in Europe. He got his training as the number three driver on the Lotus Formula 2 team. His Trans-Am experience started at the Bryar and Lime Rock Trans-Ams in 1967 in a factory Cougar. In 1968 he drove one of the factory Javelins to two seconds and two thirds, then switched to Carroll Shelby's factory Ford team for 1969. Plagued by lack of power all season, the two Shelby Fords had troubles. Revson hung on, however, to take one third and one fourth. Pete also drove a Shelby car in the 1968 Can-Am and was consistently one of the fastest five qualifiers though the car had a poor finish record until he won the Japan "CanAm" at the end of the season. Revson is a bachelor and his family is connected with the Revlon cosmetic firm.

Ford wins at Laguna Seca, Rain wins at Dallas. That's the way the first two Trans-Ams went

BY CAMERON A. WARREN and JAMES T. CROW

Submitted by Aaron Davis

Laguna Seca

"POLITICS MAKES STRANGE bedfellows", Cleopatra once remarked as she tucked a snake into her bra. And trying to administer a road racing series for production sedans results in some pretty peculiar situations, too. Particularly when the U.S. automobile industry is one of the principals and the Sports Car Club of America is another.

"The Trans-American Championship is an annual series of events for Sedan Category automobiles to determine a manufacturer (italics ours) champion in over-2-liter and in under-2-liter cars. The events are held under the SCCA General Competition Rules." Which rules I've just quoted.

After some criticism for the way things were spelled out in the past, the SCCA went to some trouble to revise the rules for 1970, presumably to the satisfaction of various interested Detroit parties. A meeting was held in August 1969, at which the production levels necessary to meet homologation requirements were agreed upon, and it was decided that ACCUS, this country's FIA rep, would verify such production. The deadline was set as 10 days prior to the first race of the season. For any model to be eligible, the quantity actually built had to equal 1/250th of the total 1969 production for that company, with a minimum of 2500. The actual figures- were 8200 cars for Chevrolet, 7000 for Ford, 2800 for Dodge, and Javelin and Plymouth 2500 each. To complicate matters, the Camaro wasn't even introduced until after the first of the year, and other companies were also lagging badly. The deadline was extended.

By the time the opening event of the season rolled around -- the Laguna Seca affair -- SCCA technical administrator John Timanus had already put in a lot of man hours, scurrying around the country, looking at assembly lines, checking warehouses, reading production reports and visiting the specialty shops where the 1970 Trans-Am racers were being built.

Ex-racer, former driving instructor (for the Carroll Shelby School) Timanus is not only highly knowledgeable about high performance machinery, but also has a large reserve of patience. Both important requirements for the difficult job he has been assigned. Diplomacy is another essential virtue for this sort of thing, as Bill France discovered some time ago. Factory coordinators, especially, get up-tight if everything isn't going their way. Frequently their attitude is, "If our team can't have a substantial advantage, we don't want to play" and gamesmanship of a high order is played by all sides.

When technical inspection opened Friday night at Monterey, the organizers weren't sure if any of the teams would make it. Ford had appeared earlier with a trick carburetor, Camaro hadn't built enough cars with the big spoilers so dear to the heart of Jim Hall, Pontiac was in a similar position, Javelin was having engine troubles, and so were the Chrysler products. But when Timanus, and a crew of inspectors for the San Francisco Region, showed up to go to work, there was one of Jim Hall's Camaros first in line. Spoiler-less at that.

After the tech crew gave the car a preliminary once over, checking external dimensions and safety features, John Timanus stepped forward with calipers in hand and measured the carburetor throat. ("1-11/16ths, right on the nose.") Yes, the windows were still in the doors and they could be wound up. Everything else looked good, and the #2 Camaro (to be driven by Ed Leslie) was given an okay sticker.

Next was the Javelin to be driven by Mark Donohue. Like the Camaro, it was beautifully prepared, but there was one small flaw that caught the eye of Timanus. "That quick-fill oil line will have to be moved to a position under the hood," he told Roger Penske; "I'll okay it for now, but have it changed by Lime Rock." Roger nodded silently and carefully folded the written citation.

Inspection was also scheduled for 7 o'clock the following morning so Ford, and the other factory teams, waited until then. There had been considerable doubt that the Bud Moore Mustang Team would appear at all. First, there was the carburetor change, then the Ford economy drive threatened the team's very existence. But when the sun rose Saturday, there was not one, but three Moore Mustangs lined up--one each for Parnelli Jones and George Follmer, plus a back-up car.

Follmer's mount, #15, was checked first. Timanus pointed out that the metal straps retaining the windshield were too short and disapproved the use of the headlight openings for ducting air to the brakes. Moore started to bluster loudly, with no effect. Then Fran Hernandez, Ford's Trans-Am Coordinator, stepped forward. With a histrionic ability that nearly brought tears to the eyes of the onlookers, he made an impassioned plea for the brake scoops on the grounds of driver safety, spectator well-being and the potential blot on SCCA's escutcheon if the car crashed. Timanus tucked the citation he was busily writing into the back of his notebook and said, "Go see the Chief Steward. If he okays it for this race, I will too. But you could move those scoops down to the spoiler, just like everyone else has done."

Hernandez went looking for Merle Stanfield and Timanus turned his attention to the scales. The Mustang weighed in at 3195 lb wet, five pounds underweight. Moore looked pained, then threw open the hood.

"Look," he cried, "no air cleaner! That weighs at least five pounds!" Timanus sighed and nodded his acceptance.

Next up was Sam Posey's Dodge Challenger, which got through the inspection with no serious problems, and then came the Pontiac Firebird of Jerry Titus. Interestingly enough, both Chevrolet and Pontiac build (or at least advertise) "Trans-Am" models but as yet neither is eligible for the series so for the moment the racers must drive plain-Jane versions. Somehow, during the night, friendly elves had fastened a big spoiler on the back of the Firebird, however. Timanus, busy explaining to Titus that the air-scoop hood wasn't legal, completely overlooked the new appendage on the rear and gave his okay to move the car up to the scale. Several minutes later, while discussing the subject of spoilers in general with a reporter, John suddenly realized what had happened and dashed after the Firebird.

Spoilers had sprouted on the Camaros, too, although they were the smaller 1969 type rather than the over-size ducktails Hall had wanted. "We've built 8200 cars with small spoilers," claimed a GM man, on "vacation" at the track. A conference call was placed to John Oliveau, executive director of ACCUS, and the situation explained. ACCUS and SCCA were willing, nay anxious, to give Chevrolet every possible break, but rules were rules. The Camaro teams were advised that if Chevrolet was unable to conclusively prove they had met the production requirements as of that moment, the penalty would be "severe."

Under those circumstances, nobody in the Chevrolet camp was willing to stick his neck out that far, and the spoilers came off.

Meanwhile, Chief Steward Stanfield had backed up Tech Inspector Timanus and the Moore team was busy rerouting the brake scoops. A private entrant had found a new bottom plate for his carburetor, so it was legal, and an Alfa driver had found the right FIA papers so his car was cleared to run in the under-2-liter race. All cars had passed the weight check, although it was interesting to see how close they came to the minimum. All in all, 21 cars were inspected and approved for the over-2-liter event, and the inspection team could grab a hot-dog and relax for a couple of hours.

The racing during this first Trans-Am showed that the Bud Moore Mustang team was starting out with a definite edge. Parnelli Jones was the fastest qualifier (1 min 11.90 sec) ahead of Mark Donohue's Javelin (1:12.36) and won the race in the handiest possible fashion. Donohue finished second and George Follmer was 3rd in the other team Mustang. These first three positions were established from the start but there was some shuffling about from there on. Dan Gurney qualified fourth ( 1:12.74) and then ran fourth in his Barracuda for a while but dropped out with clutch trouble after 24 laps. Teammate Swede Savage in the other Barracuda kept going to finish fourth. Among the Camaros, Ed Leslie qualified 6th-fastest (1:13.45), dropped back with a flat tire in the early laps, moved to 5th by midrace and retired shortly after that with a broken wheel. Jim Hall, who qualified 10th (1:15.84), lasted only three laps before retiring with gearbox trouble. Milt Minter, driving an independent '69 Camaro, finished 5th overall and Sam Posey, driving the Challenger entry, was 6th. Peter Revson, driving the second Javelin for Penske's team, quit after 20 laps with brake and suspension troubles. Jerry Titus's Firebird, scoopless and spoilerless, was 7th fastest in qualifying (1:14.07) and finished 7th in the race.

After the race, it was back to work, checking the winners. The first five vehicles were weighed again and their engine displacement checked with an overgrown stomach pump device known as a "P&G Displacement Tester." Certain engines -- one of each manufacturer in the first five -- were torn down, and the bore and stroke physically measured. They all passed and the results were made official.

Then, to their collective horror, SCCA officials noticed something. A clear violation of the Supplementary Regulations which clearly stated that all cars must bear a decal of the SCCA emblem, together with a decal for the series, in this case, the Trans-Am Championship. The first four cars were in flagrant violation. For a moment, it looked as though they might be disqualified and 5th-place Milt Minter declared the winner but reason prevailed. Chief Steward Stanfield had the solution.

"Tell them," he announced, "that if anyone shows up at Dallas without his SCCA decal, it will cost him a hundred dollars!"

Laguna Seca Trans-Am - Monterey, Calif. - April 19, 1970

Driver ----------- Car ---------- Laps

1 Parnelli Jones -- Ford Mustang -- 90

2 Mark Donohue -- AM Javelin -- 90

3 George Follmer -- Ford Mustang -- 89

4 Swede Savage -- Barracuda -- 89

5 Milt Minter -- Camaro -- 88

6 Sam Posey -- Challenger -- 87

7 Jerry Titus -- Firebird -- 86

8 Craig Murray -- Camaro -- 84

9 Joe Chamberlain -- Camaro -- 81

10 John Silva, Jr -- Camaro -- 80

11 Jerry Oliver -- Camaro -- 78

12 Wes Dawn -- Mustang -- 74 laps.

Distance: 90 laps of 1.9-mile circuit, 171 miles

Avg speed: 91.375 mph.

Fastest lap: 1:31.01, 93.672 mph, Jones

Retirements: Craig Fisher, Firebird, 60 laps, engine; Ed Leslie, Camaro, 59, broken wheel; Bob West, Camaro 43, overheating; Hugh Harn, Camaro, 33, headgasket; Dan Gurney, Barracuda, 21, transmission; Peter Revson, Javelin, 20, brakes; Frank Search, Camaro, 13, engine; Bob Kennett, Mustang, 5, wheel bearing; Jim Hall, Camaro, 3, transmission.

Dallas

THE SECOND Trans-Am of the season was scheduled for Dallas International Raceway. By the time its indefinite postponement was announced at 10:45 Sunday morning, one incontrovertible fact had emerged. If you work hard enough, you can build a new racing circuit and get it finished just barely in time. Or you can have a Texas-style spring shower that brings eight inches of rain in less than 12 hours. But you sure can't have both and still put on a race.

If there hadn't been any rain at all over the weekend, there would still have been plenty of problems with the new track - dirt and gravel from the loose shoulders, mainly, but also with the minimal distances an off-course car could go before either getting into a guard rail or going over a bank. The rain simply made it impossible.

The first storm came at about four o'clock Saturday morning with lots of rain and with tornadoes dipping to earth nearby. There were two more heavy storms during the day and at 2:45 Saturday afternoon the rest of the day's activities were cancelled with the promise that everything would resume on Sunday morning.

Even before this, however, things hadn't been going well. Course workers were sinking out of sight in the mud, emergency crews were wondering what they'd do if a competitor was to leave the circuit at speed in one of the flooded areas and the only spectator areas that could be used were in the paved and graveled sections at the tower end of the course.

The cars had gotten out for brief periods before this, the under-2-liter cars for two sessions, the 5-liters for one. The circuit was mostly dry while the big cars were out and Parnelli Jones and teammate George Follmer in their Bud Moore Mustangs were easily the fastest with Sam Posey's Challenger next. The Penske Javelins didn't get out at all as they arrived late, the same for Jerry Titus's Firebird.

But it didn't really matter, even though no more real rain fell after the afternoon storm on Saturday. The drainage took care of that, more water pouring into the property from upstream than could be drained off. By midnight, the water level was higher than it had been during the rains but it was hoped that dawn would find the waters at a lower level.

The next morning, however, it was even worse and the water had risen to within a few feet of the course in some places. The cars were ready in the pits, the Texas and San Jacinto SCCA Region workers manned their stations, loads of haybales were dispatched to the critical areas to be used as temporary barriers and the sky lightened. Nine o'clock, the scheduled hour, came and went. Then ten o'clock and by this time everything was ominously quiet. Finally, at 10:35 the drivers and entrants were called to a meeting at the start-finish line and there they were informed by chief steward Merle Stanfield that the stewards of the meeting had decided that the races could not be held and that the event would be rescheduled later, if possible. There were no outcries, no remonstrances, not even more than one or two questions. Later there were grumbles because the decision was so long in coming but no one disagreed that the stewards' decision was the correct one.

Entry fees were refunded to the competitors, as required by the SCCA rule book, and the Dallas International management offered cash refunds to spectators if they would mail their tickets in. It was an historic occasion, the first professional SCCA race not to have been run on the scheduled day, but no one was happy about it. As the competitors re-packed their gear, loaded their cars back onto the transporters and began to think about Lime Rock, the sun was coming through and it was soon steamy and hot. But it didn't do any good. The waters were still high, the high ground had been abandoned to the snakes and the Dallas Trans-Am was not to be.

Javelin Becomes a Trans-Am Winner

The Javelin is a winner. The judgement of team manager Roger Penske and driver Mark Donohue, when they decided to field a two-car team of Javelins for the 1970 Trans-American season, was vindicated June 21. On that rainy Sunday afternoon, Mark Donohue won at Bridgehampton. Mark's victory was the first for Javelin in the highly competitive Trans-Am series.

Donohue drove the 199.5 miles in 2 hours, 12 minutes, and 43.3 seconds, averaging 90.55 miles an hour. He finished a comfortable two laps ahead of Mustang teammates George Follmer and Parnelli Jones.

Donohue won despite pressure throughout the race from either Swede Savage in a Barracuda or Jones in the Mustang. He also had to contend with heavy rains that began falling on lap ten of the 70-lap event.

Donohue qualified for the race in second position, only .3 second off the pace established by polesitter Savage. At the start, Savage and Jones, who started third, grabbed the first two places, but Donohue was right behind. Donohue moved into second on lap 12 and into first on lap 27. He was to lead the rest of the race.

It looked like the Penske team finally had put all the pieces together in just the right way that makes a winner. But the next race, at Donnybrooke, Brainerd, Minn., on July 5, was to be a disappointment. The engine on the Javelin Donohue was driving failed on the 14th lap and he was put out of the race.

If there was a consolation, it was that the other major entries also suffered problems, and Milt Minter, in an independent Camaro won the race.

Donohue had qualified fast enough for fifth place when his car quit on him on Saturday. The crew spent many hours replacing the engine, only to have it also fail on Sunday morning.

When this happened, Donohue took over the twin Javelin that was to be driven by Peter Revson.. As the Sunday morning practice session ended, Mark was running laps as fast as the polesitter, who was again Swede Savage in a Barracuda.

As the race began, Mark battled for the lead in the red, white and blue Javelin. He was in contention until that fateful 14th lap when he retired.

After the sixth race of the 1970 Trans-Am series, Javelin stands third in the manufacturers championship with 25 points to the 48 points of Mustang and the 26 points of Camaro. Challenger and Barracuda are a distant fourth and fifth with 7 and 5 points respectively.

As we go to Press...

The Sunoco/Javelin driven by Mark Donohue took first place in the Road America Trans-Am on Sunday, July 19th at Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin. The win puts American Motors in second place in the 1970 point standings. Donohue finished 68 seconds ahead of Swede Savage, who was driving a Plymouth Barracuda. Sam Posey in a Challenger was third. Camaro was fourth and Parnelli Jones' Mustang was fifth. The next race will be in St. Jovite, Quebec on August 2nd.

Javelin: A Racing Success Story

submitted by Pete Harrison

Or how the little guy of the American automotive industry got the big guys running scared in the racing world.

JUST THREE short years ago, American Motors, the smallest of the automobile manufacturers, decided to go racing with their newly introduced pony car, the Javelin. After much consideration, the company decided to make their effort in Trans-American sedan racing, rapidly growing in popularity.

Armed with enthusiasm, an untested product and optimism, the red, white and blue cars began the 1968 season, with Traco built engines, Kaplan built cars and Peter Revson and George Follmer doing the driving. The season was expected to be exciting with the Penske and Shelby Mustangs with Jerry Titus and Horst Kwech doing the driving and American Motors as the brunt of all the jokes.

By mid-season, everyone realized that American Motors was no longer a joke as they and Ford were doing battle for second place in the point standing. Mark Donohue was making a runaway for the championship, but Ford was concerned about this upstart who dared challenge them, and was forced to bring in drivers like Parnelli Jones, David Pearson and Dan Gurney to help the regulars. The second place see-sawed back and forth all season as the fans were eating this up and Javelin was making its presence known. Its all history now, but they did end up in second place and the future looked bright for American Motors.

In 1969 they expanded their efforts into the NASCAR Grand Touring (now called Grand American) circuit when they reached agreement with Warren Prout to build a car and Jim Paschal to drive. Revson and Follmer were gone as their Trans-Am drivers. With this expanded effort and a reputation from the 1968 season to uphold, they were struck by the sophomore jinx that seems to be common in sport. As a result, everything wrong began to happen and the season ended less than successful.

Then came 1970 and racing history was made with a news item: "Penske/Donohue sign with American Motors." The team that had completely dominated Trans-Am for the past few years was quitting Chevrolet in favor of Javelins. Jim Hall took over the Camaro's efforts, but they became an unimportant factor during the year. Actually, the team to beat was Ford Mustang with Parnelli Jones and George Follmer handling the driving. With a brand new car, breakage became a major problem for the Penske/Donohue team for the first half of the season, but then the combinations started working and they began to win and chase Ford. With two races remaining for the season, Javelin still had a shot at the championship but again problems beset the team and they ended the season in second place, a position Penske and Donohue are not familiar with. Judging by the reputation of this team and what they learned in 1970, I would say watch out for them in '71.

In the meantime, down south, Jim Paschal was running a Javelin on NASCAR's Grand American circuit. There are many more races on the GA circuit and for the first part of the season, Paschal kept hanging in there, but Tiny Lund was having an unbelievable streak of good luck and winning race after race. Finally the streak ended and Paschal began to win races and close the gap for the points championship. As of this writing, there are still a few races to go, and it is doubtful that Paschal will be able to catch Tiny Lund, but still it was American Motors most successful year on this circuit. All in all, 1970 must go down as the most successful for American Motors. Can David beat Goliath in 1971... only time will tell.

-Paul Haluza, Publisher - STOCK CAR RACING

Ford would win the 1970 Trans-Am Championship. Parnelli Jones would win the Driver's Championship over Mark Donohue - by one point, making it the closest Drivers' Championship ever. Javelin took three victories and would finish second in the 1970 Manufacturer's Championship.