Site Tools & Extras

Quick Links

1968-1972 Trans-Am Racing

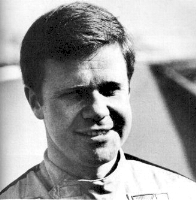

Mark Donohue Tribute

Mark Donohue - 1937 to 1975

One of the prerequisites for a professional race driving career is not a college education. But it can help.

Mark Donohue (Brown '59) is a case in point.

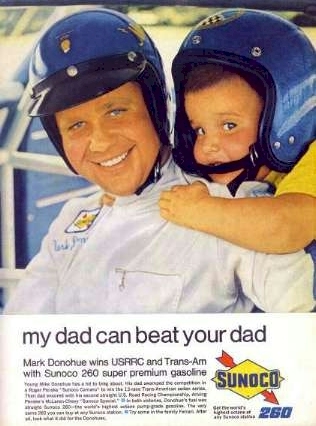

The quiet superstar of Roger Penske Racing Enterprises and the Sunoco-Javelin for American Motors in the Sports Car Club of America's 1971 Trans-American Sedan series is a practicing engineer who does some of his most important work at 200 mph.

Thus, it is not likely there is any driver in the world who is as intimate with his automobile as Donohue.

"One of the reasons Mark is so good is that he can evaluate what we're doing on the drawing board," said car-owner Penske, "then see if it works exactly as it should on the track."

Donohue, who is 34, is part of an engineering team for Penske that includes Don Cox, 31, and general manager Chuck Cantwell, 36. All three are graduate engineers who support their design and development work by computer.

It is as a driver, of course, that Donohue has provided a rare stability to the Penske team.

"You might call him a built in reliability factor," says Penske. That is, Donohue does not abuse the vehicle. In fact, he has been described as "intense but not tenacious" on the track. He drives to finish, yet he never hangs back.

Penske, who has always contended that Donohue is the most underrated driver in the sport, also says "he is the most consistent race driver in the business."

"He is not driving at 102 per cent over his head, that is," Penske remarked, "but at 98 per cent. There's always something in reserve.

"Remember, first you must finish to finish first."

Donohue and Penske exhibit a driver-team manager relationship in racing that is most unique.

"It's perfect for a lot of reasons," says Penske. "We're the same age. He's like my brother. Mark is a dedicated, honest person who never tries to put himself out in front. I respect him.

He's been a tremendous asset from the beginning. He fills a void. Really, we complement each other."

The two men do have divergent personalities. Penske is outgoing. Donohue is quiet, sometimes unapproachable due to his intense manner in his work. He reserves conversation for the things that are worth saying, or needs to be said. When the time is right, he can be witty . . . albeit, a dry humor.

Even Donohue's rivals admit they don't really know him that well.

Actually, there's a "new" Donohue on the circuit this year. No longer can he be described as a crew-cut All-American boy. He has let his hair grow. Long by his standards, it would still pass inspection at a Marine boot camp. No, Donohue hasn't gone "mod" for '71.

His appearance, however, remains disarming. He simply doesn't look like a hardened race driver, a fact that somewhere along the way earned him the nickname of "Captain Nice."

As a disciplined driver and man who keeps his cool when others around the course are losing theirs, Donohue seems an unlikely sparring partner for some of racing's "tough guys."

In last year's Trans-Am series, while winning three races, he accumulated only one less point in driver standings than champion Parnelli Jones, who definitely is a hard charger on the track. The competition between the pair was fierce.

"I don't care what people think, Donohue is no angel out there," Jones has commented.

If Donohue isn't a loud voice in his own behalf, his record is.

In 1959, he entered his first sports car competition in a Corvette. And he won. He won a SCCA national amateur title in 1961. In 1965, he won two SCCA championships and was named "Driver of the Year."

Last year, Donohue presented American Motors its first Trans-Am victory, then its second, for a record of 20 Trans-Am victories in three seasons. He carried American Motors to second place in competition that included all U.S. manufacturers. Also, Donohue was second behind Al Unser in the Indianapolis 500.

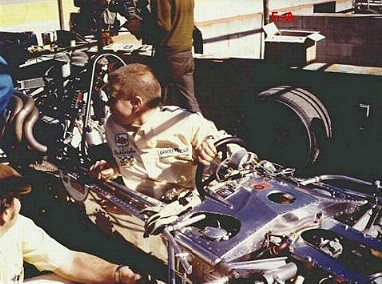

Donohue's co-workers call him a perfectionist, explaining why he spends so much time testing and participating in the design of the race cars he drives.

He once said: "The problem with most drivers is that they don't know what their cars will do. The driver must know."

Donohue's racing philosophy is "testing is the key." He estimates he puts two miles on the test track for every one mile on the race track.

As a result, his personal schedule is demanding. For example, he recently drove in three major races within eight days ... all different types of race cars. He was testing constantly in between those events.

The penalty of such a schedule for the native of New Jersey who now lives in Media, a suburb of Philadelphia, with his wife, Sue and two sons, "is not enough time to spend with my family."

Why then does he push himself at such a furious pace?

"This is a tough business," he explains. "To do it unsuccessfully is the worst. To do it successfully is the best."

Auto Racing Digest - January, 1976

"If I get wiped out and they carry me away, I wouldn't expect anybody to feel sorry for me. It's something I know is a possibility. I'm not complaining." Mark Donohue, 1974

A Final tribute to Mark Donohue - By Harvey Duck contributing editor

America's greatest road racer, "a correct" man, will be missed by a fraternity that loved him as few others.

Racing celebrities tend to wear different faces for different purposes. There's a smile and an autograph for the spectator, a growl and a cussword for the officials, a word of praise for a rival driver, a cryptic comment to the crew member. The auto race driver usually sees and hears a bit of each so the real personality is partially camouflaged and seldom emerges. Not so with Mark Donohue. He never varied, he was to everyone who knew him intimately or casually, the same gracious gentleman who was more concerned with your moods than with his.

Donohue contributed far more to racing than he received. But the tragedy of the imbalance is that most people - even those in racing - overlooked that fact in the media wake of his death last August.

It was shortly before the crash of his Roger Penske owned car during practice for the Austrian Grand Prix that Donohue confided, "We have discovered some things will really make this competitive in Formula One racing. I'm really excited about the future."

It was his love of mechanical perfection - as much as a physical challenge of driving - that prompted Donohue to become a professional race driver. He won, during an all too brief career, 57 major events in a variety of cars and competitions. He drove - successfully - Camaros, Javelins, Matadors, Lolas McLarens, Porches. Invariably, he drove them not only quicker than they had been running, but with a degree of skill that kept them competitive at the finish as well as at the start.

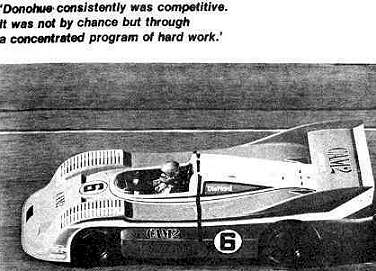

That consistently high degree of competence was no accident. It didn't come by chance, but through a concentrated program of hard work "Mark knew where every bolt, nut and spring was on every car he drove," recalled teammate Bobby Allison. "And, he not only knew where they were located but what they were supposed to do and if they were doing their jobs. If not, he wouldn't drive the car. He simply would not over-extend a piece of machinery that he didn't have the most confidence in.

"He was, I feel, the finest road race driver that this country has ever produced and given enough time - just one more year, maybe - he would have become America's first World Champion".

Most of Donohue's victories were as precisely orchestrated as a Russian ballet performance and with the exception of the truly "major" triumphs, such as the 1972 Indy 500, they tend to blend into a fellows memory like a montage.

Yet, one that stirs especially fond recollections came in the 1973 Canadian - American Challenge Cup series. It was a blistering hot August afternoon at the four-mile Road America course in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin.

Donohue, in the cockpit in the monstrous 12-cylinder Porsche-Audi 917-30 (the same car in which he set a worlds record of 221.160 miles an hour - two years later) simply overwhelmed his opposition.

His average speed of 114.580 in the feature race shattered every track mark. His 122.535 in the qualifying run in a time of 1:57.51 was the first sub-two minute lap that Road America had ever seen.

The pavement was hot, slippery and treacherous as the heat inside the car rivaled a Finnish sauna - so suffocating that Donohue nearly collapsed from exhaustion between races. Yet, that calculating mind of his remained as cool as an ice cube in the midst of the mini-inferno.

"The question today, really, was not how fast I could drive the car," explained Donohue weary but composed after his victory, "because turning in quick laps for a short time is one thing. But, to run fast for 200 miles is something else. The car, as it was set up, did exactly is it should have. I mean, it did what I expected of it.

"But, give me another day or two of practice here and I'd of gone faster. That's what I mean about not approaching the cars potential." That, perhaps better than any other summation, explained Donohue's racing creed:

- The car did what he expected of it.

-The potential must first be approached before he could go faster.

Still, that eagerness to narrow the gap between potential and ultimate performance did not dim Donohue's awareness that increased safety measures were needed. He stressed, before a 1972 International Motor Press Association panel discussion that, "safeguards must be adopted to protect a driver in the event of an accident".

Few people - even those deeply involved in racing - were aware of the close relationship that existed between Donohue and Penske. It was assumed, and correctly, that they got along well and that a Penske-owned car, prepared and driven by Donohue, was a genuine threat in any race entered.

It was appreciated that the pair often introduced innovations that brought out the best in their cars and equipment. Yet, they formed a contrasting marriage.

Penske, a bundle of never-ending energy, was always on the move. He enjoyed the exposure to the news media and the public and those of us privileged to be invited behind the Penske perimeter often chuckled at the ease with which he manipulated his image.

Donohue, during his first competitive seasons, was cast in another mold. He seemed to neither enjoy nor dislike the frequent exposures to the probing finger of publicity, but rather tolerated it as a necessity.

Always pleasant and calm - almost serene at times - he would thoroughly ponder each question before launching his reply. In recent years, though, he became more relaxed at such times and willingly participated in the banter and jibes that sometimes accompany post race interviews.

But, once the garage door was closed to prying eyes, the pair exchanged and then expanded on one another's mechanical know-how.

There were periods of disagreement, but never of dissatisfaction. Once the decision was made - regardless of who advanced the original thought - complete agreement existed until the concept was proved correct or occasionally inaccurate.

It could, in a sense be construed as Donohue's epitaph: "He was a correct man."

Ask someone who knew him.

Mark Donohue's Career Highlights

1959 - Won hill climb in Belknap, New Hampshire driving a Corvette, his first competitive event.

1961 - Won SCCA National E-Production Championship.

1965 - Won SCCA National B-Production Championship. Won SCCA National Formula C Championship.

1966 - Joined Roger Penske Racing Team.

1967 - Won SCCA U.S. Road Racing Championship.

1968 - Won SCCA U.S. Road Racing Championship. Won SCCA Trans-Am Championship.

1969 - Rookie of the Year at Indianapolis 500 (finished 7th). Won SCCA Trans-Am Cha mpionship.

1971 - Won Schaefer 500 at Pocono. Won SCCA Trans-Am Championship.

1972 - Won Indianapolis 500.

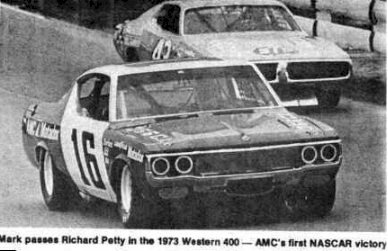

1973 - Won Winston Western 500 stock car race at Riverside, California.

1974 - Won International Race of Champions at Daytona. Retired in February. Returned to racing for Canadian Grand Prix in September.

1975 - Established world closed course speed record.

Mark Donohue's Trans-Am racing history is as follows:

1967 - Three wins

1968 - A record ten victories in 12 races, including eight straight (a record that would stand for 29 years, until 1997, when Tommy Kendall would win 12 straight).

1969- Six wins

1970 - Three wins

1971 - His final three wins

In 55 races Mark Donohue had 29 wins with 3 top-three finishes. He finished on top of the drivers' point standings three times, with two runner-up positions.